By Jim Eaton, Jr., grandson*

Relation to Andy and/or Flora Lehr

This post is a collection of articles from a personal history project completed by James A. Eaton, Jr. It is posted with his permission.

INTRODUCTION TO MY STORIES

Several years ago, my son, Jamie, gifted me a subscription to StoryWorth for Father’s Day. This suggested to me that he has some interest in learning about my early years.

For years, I have been recording memories of my life. However, I kept stalling out. StoryWorth’s weekly topics provided direction and stimulation to get each story on a specific subject completed. While this compilation of stories cannot encompass all aspects of my life, it provides a good picture of major events and people in my life and issues I want to pass on to future generations.

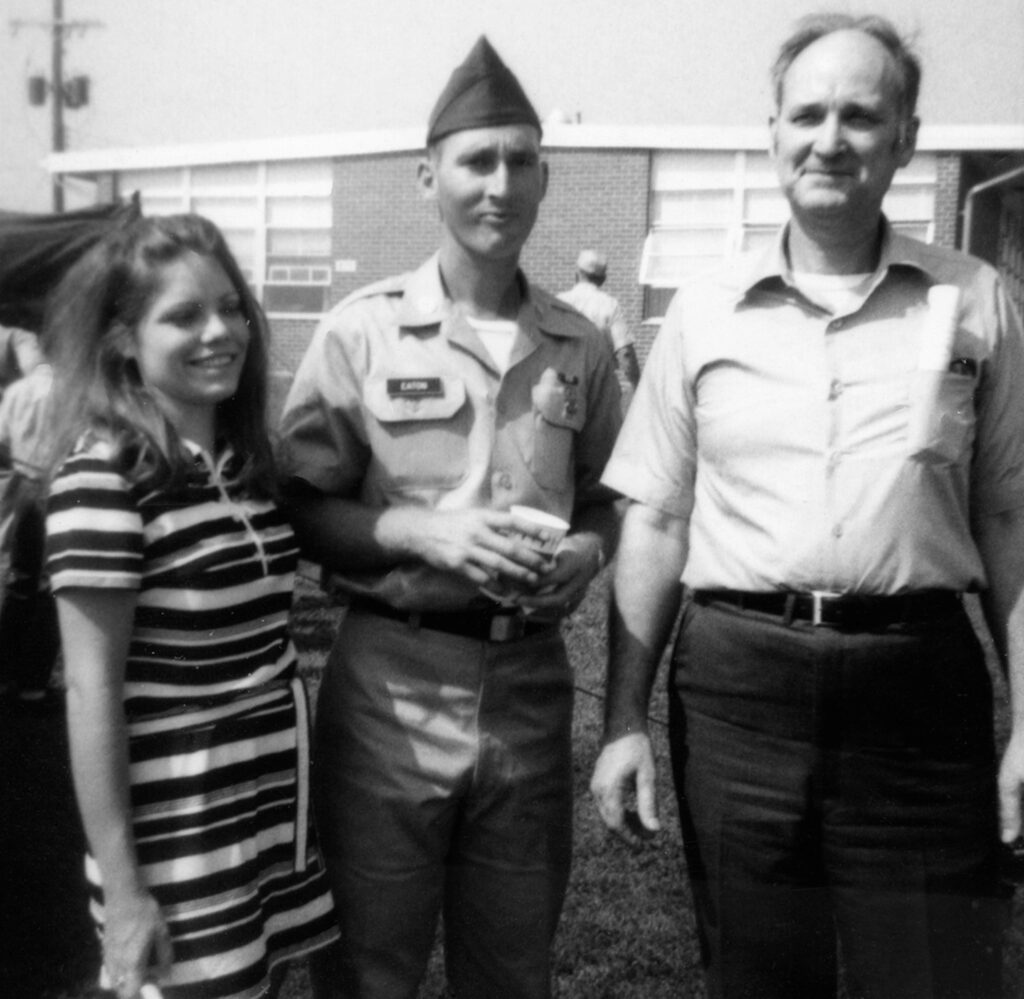

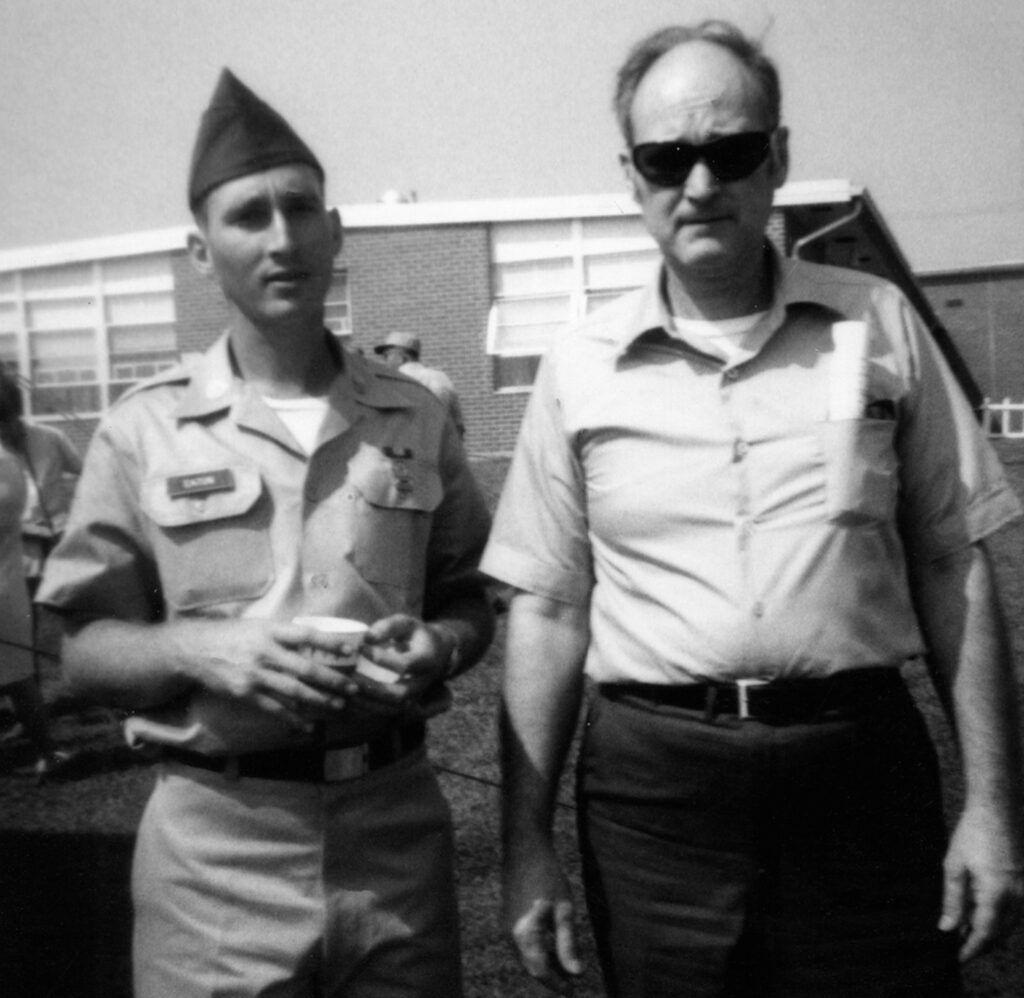

I spent considerable time with my father. However, most of the time was at work, and most of our conversations were work related or relevant to life issues. Seldom did he talk about his youth, and far less about his military experience. Now that those issues are of paramount interest to me, I have little source material and essentially no witnesses to provide insight into them. I learned of the great hardships he and his family endured in his youth. By inference, I know the personal strength, determination, and character he must have had to not only endure such, but to excel and do so without any animosity.

While I have had a great life with mere bumps in the road compared to his, I thought my descendants might have an interest in what made me what I am. It might give Pam some insight into my quirks and idiosyncrasies. So, I am deeply indebted to Jamie for this gift, and extremely grateful for his thoughtfulness. Because he gave it to me, I have done my best to provide stories that will be informative and interesting to him.

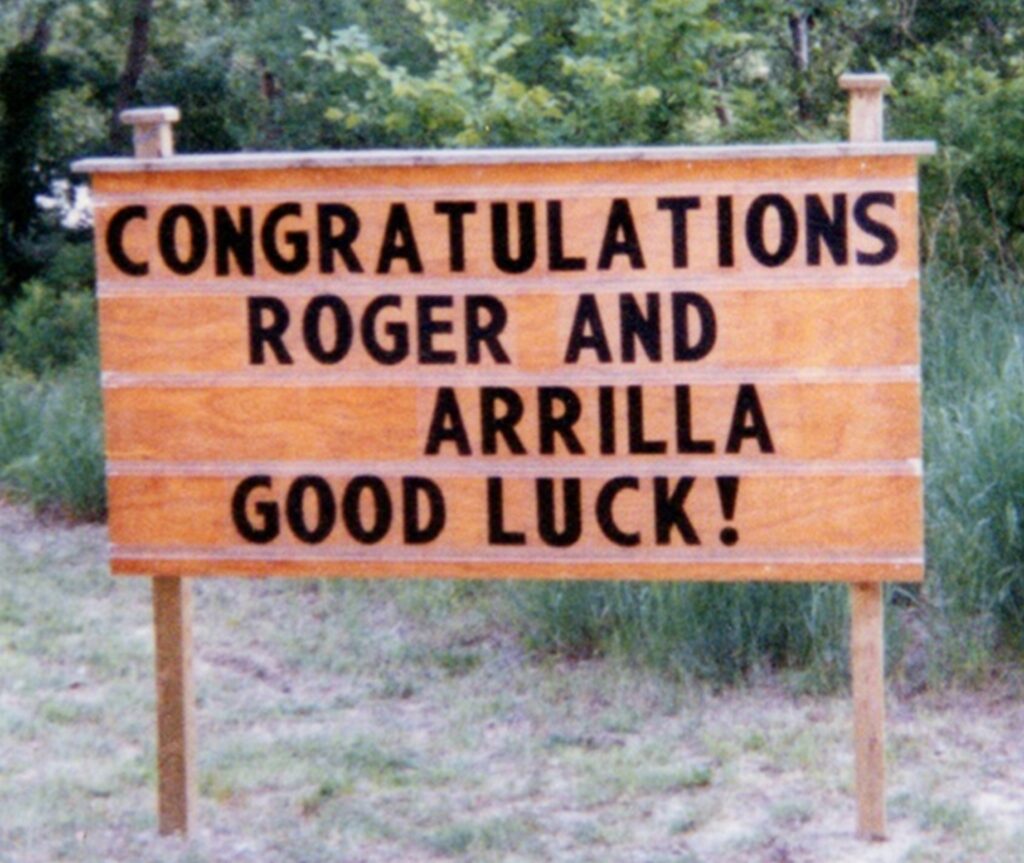

I must acknowledge and extend my sincere appreciation to my “editors” my wife Pam and my youngest brother Roger. Their input was invaluable.

Why did you join the military?

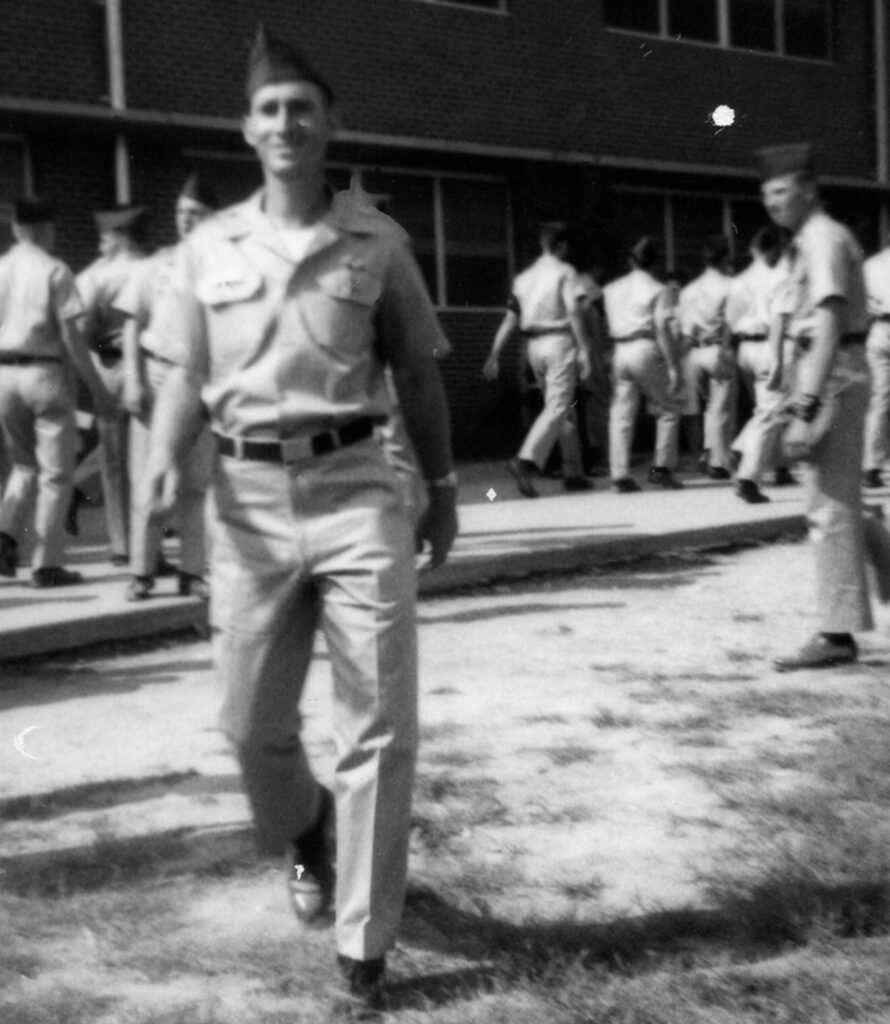

When I graduated from high school in 1964, the conflict in Vietnam was escalating. All males were required to register with the Selective Service System. It was from this database that local draft boards would decide who would be called upon to serve their country. Each year as the conflict intensified, more and more were called into the service of their country. Initially, college students and then married individuals were given deferments, the latter changed as the need increased. I received a deferment throughout my five years of undergraduate study. On December 1, 1969, the first draft lottery since 1942 was held. I won. My number was 17! They took the top 95. At that time, I was living in Knoxville, Iowa. My draft board in Butler County, Kansas had no difficulty locating me.

When I received my notice, it was accompanied by a directive to report to the AFEES station in Des Moines, Iowa. The AFEES station was the induction center where they gathered more personal data, and conducted physical examinations. It was also the point of disembarkation to basic training. When I reported to the AFEES station, I found it over crowded. The demand for military troops was so great that they lowered the basic requirements to entry into any of the branches. In all of the hundreds of men who underwent physical examination that day, I saw only a handful who failed. After passing my physical, it was apparent that I had ten days to either enlist or be inducted. I choose to enlist for three years in a program that delayed entry for 90 days, then attend Officer Candidate School (OCS). In the interim, we moved to Great Bend, Kansas where I drafted a policy and procedures manual for Larned State Hospital and the Kansas State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

During this time, there was major unrest in this country over the Vietnam conflict. Demonstrations and protests were occurring on many college campuses. There was rioting in some cities. Soldiers in uniform were verbally and physically abused. The military was not viewed as a desirable profession. Many of those who won the lottery moved north of the border to Canada.

When I reported back to the Des Moines AFEES station after 90 days, I was advised they had no record of any commitment for OCS, just a three year commitment. To say the least, I was not happy. Frankly, I was intimidated to go ahead with my enlistment. I was able to negotiate my advanced training. This time I got it in writing—medical technology school. In retrospect, missing out on OCS at that time may have been a life saver. Most of the young second lieutenants graduating from OCS went directly to Vietnam. The life expectancy of second lieutenants in Vietnam was very short.

When I left Des Moines for my first station, Ft. Leonard Wood, I flew into the old downtown airport in Kansas City, Missouri. Mechanical trouble delayed our departure from Kansas City. Eventually, a number of small aircraft were chartered to convey us to Ft. Leonard Wood. The plane in which I flew was a four passenger, single engine private plane. We left Kansas City at dusk and arrived at Ft. Leonard Wood after dark. I had no idea where I was, and really never got geographically orientated.

“Why did you join the military?” The best answer to that question is that I enlisted to have some control over how I served.

What was your role in the military?

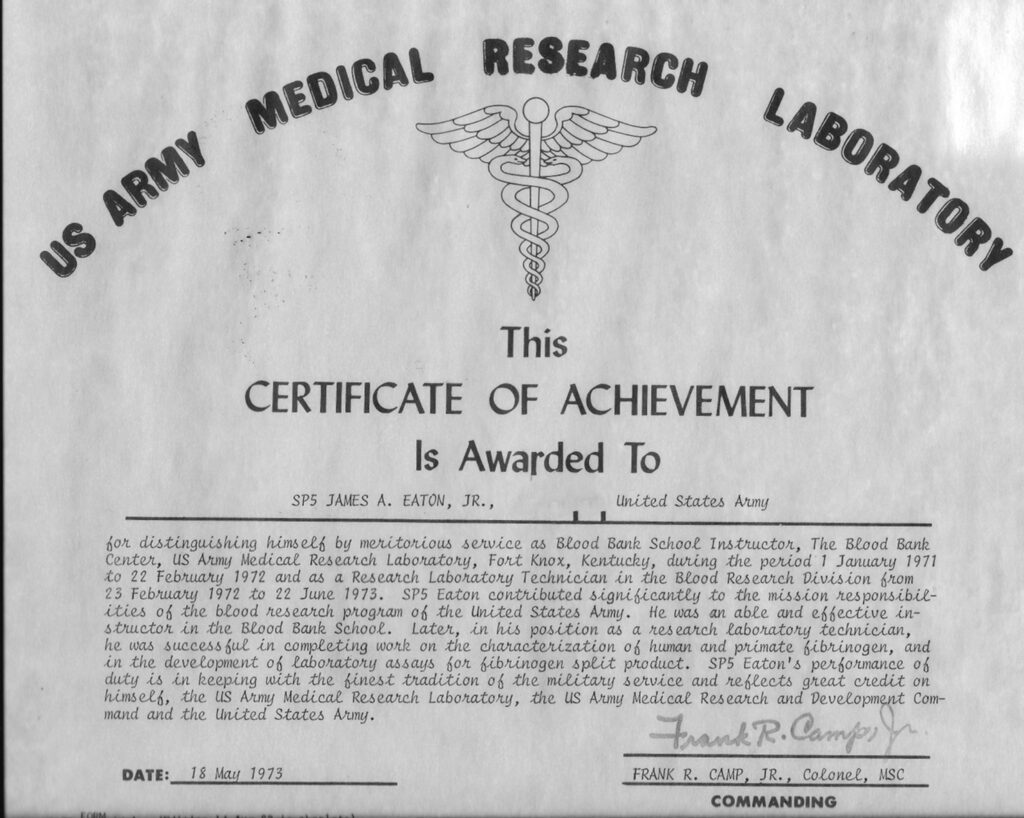

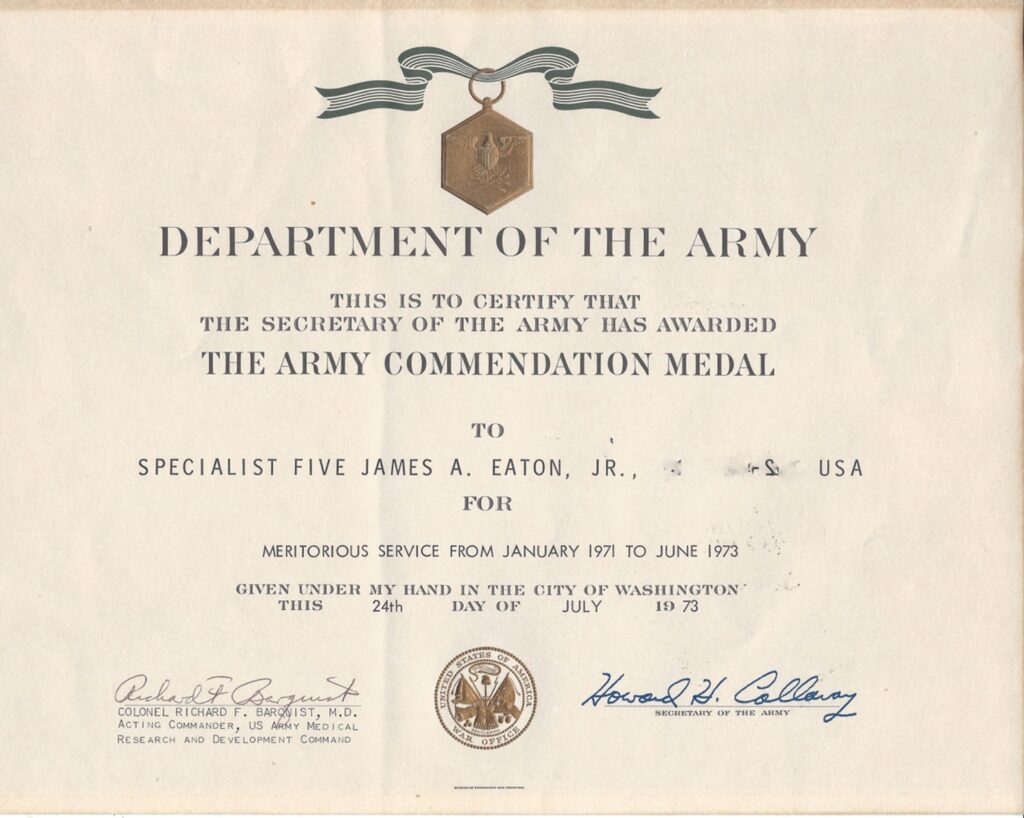

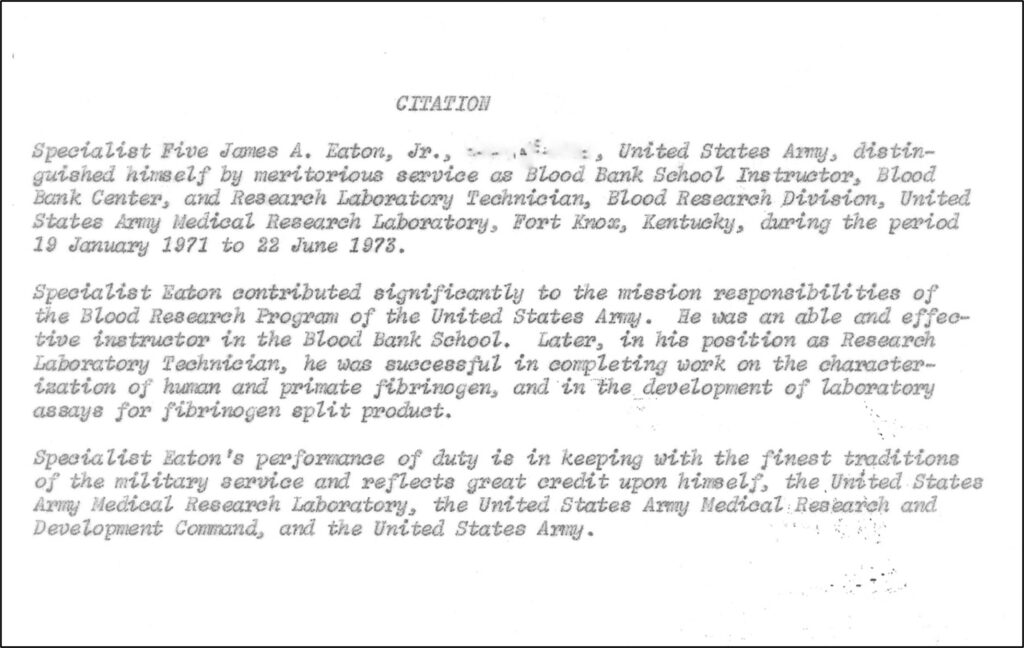

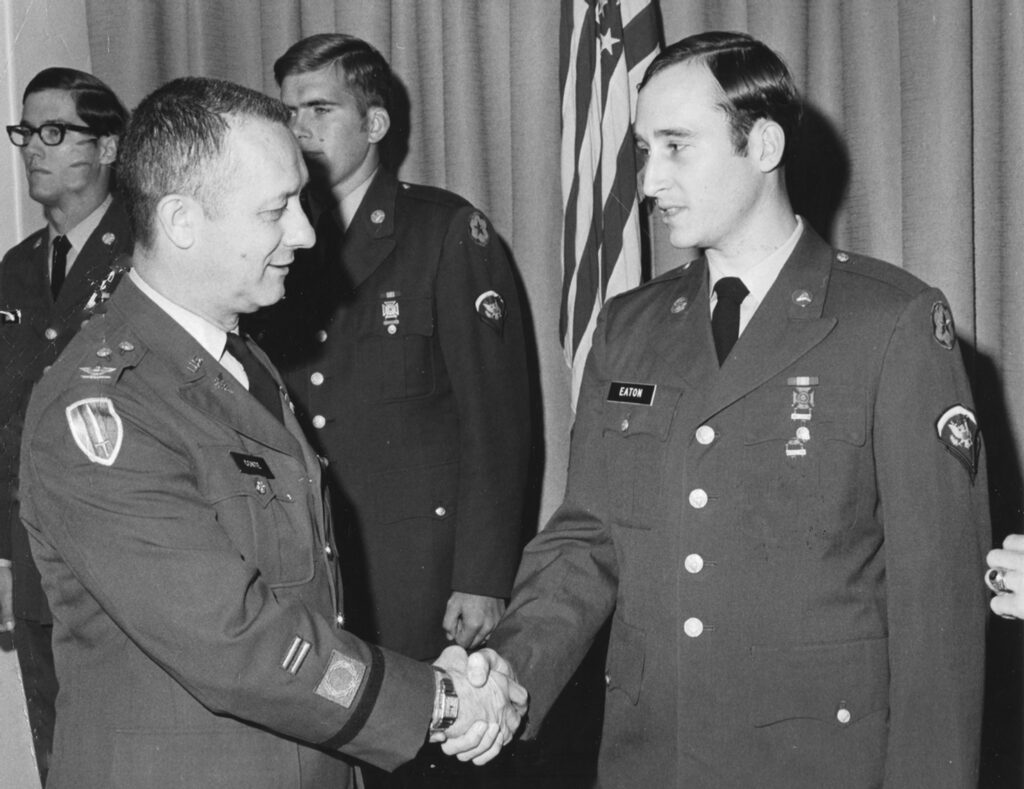

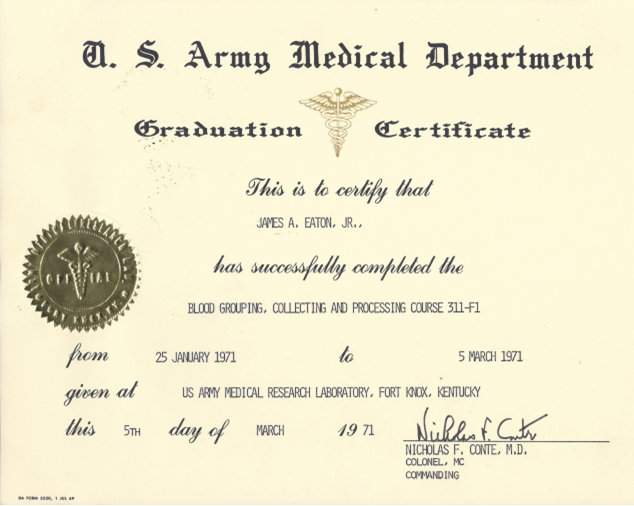

After completion of basic training at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri, the schools for battlefield medic and medical technology at Ft. Sam Houston, Texas, and the course for blood banking and immunohematology at Ft. Knox, Kentucky, I was stationed at the USA Army Medical Research Laboratory at Ft. Knox for the remainder of my three year commitment. The Lab was unique in that it was under the direct control of the Surgeon General and not the base commander. Initially, I was assigned as an instructor in the Blood Banking and Immunohematology Division. Every six weeks, we trained 20 students to obtain and test human blood, and to process it into various components. I believe we were the largest source of blood and blood products for the Army during that time—remember this was the early 1970’s and the Vietnam War was still raging.

Because of the time crunch, I was assigned to attend the Staff and Faculty Development School at the Armor Division at Ft. Knox, instead of sending me back to Ft. Sam’s Medical Staff and Faculty Development School. It was interesting and an education in itself. Among other things, I saw the implements of war that inflicted the human carnage I was trained to treat as a medic, but that is for another story at another time.

The program I taught included didactic classroom work explaining the various blood components, storage requirements and methodologies, relevant genetics, blood groups and types, the purpose of typing and cross-matching blood, the theory behind Rh incapability in pregnancy and use of RhoGam to treat it, complications and treatment of transfusion reactions, and ethics related to the field. It also included practical application of screening potential donors, drawing units of blood from donors, typing and processing units of blood, separation and processing of blood components, including Cryoprecipitate (Factor VIII), platelet packs, and packed red blood cells.

The students were also exposed to experimental techniques being developed at the facility. This facility was the cutting edge in blood banking. It ran what would now be considered beta testing for auto-analyzers for blood grouping and typing. It developed a radio-immuno-assay (RIA) specific for hepatitis antigen. Until that test was certified, the only method to screen for hepatitis was to allow the blood to separate and compare the color of the plasma to a standard yellow chart called the icterus index. That method was very unreliable and a lot of hepatitis contaminated blood was administered—one of my close friends contracted hepatitis that way after being wounded in Vietnam. Work was also being conducted on ways to freeze and reconstitute red blood cells.

After several class cycles of six weeks each, I started part time in the Blood Research Division as a research associate, then moved there full time until I separated from the Army in February of 1973. The major project on which I worked was to develop a monkey model for disseminated intravascular hemolytic reactions due to incompatible blood transfusions. I was specifically tasked with comparing and contrasting human and monkey fibrin, fibrinogen, and their split products. This lab was well funded and equipped, and had outstanding civilian support. Cutting edge techniques were being developed and used there. I worked with an excellent hematologist, Jerry Roth, M.D., and a very fine immunologist and great electron microscopist. I learned about immuno-electrophoresis, high speed gel centrifugation, gel chromatography, immuno-fluorescent microscopy, and raising antibodies to be used in some of the above tests. I developed a latex fixation test to measure the split products of fibrin in the blood. This experience created a very strong foundation not only for graduate school, but also for what was to become my life’s profession after graduate school.

Dr. Roth had a hematology clinic once a week. He saw unusual cases referred to him from the hospital, Ireland Army Hospital. I did the blood workup for him. He was extremely generous with his time and knowledge and would explain each case. During that time, I read most of “William’s Hematology” and “Hematology” by Winthrob. I left there with a very good knowledge of blood disorders and interpretation of tests to diagnosis them.

Soon after I transferred to the Blood Research Division, I started my continuing education. This included Army correspondence courses in advanced medical technology, and at workshops both in the Army and at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. This facilitated my advancement to E-5 within 18 month of my enlistment. E-5 was the highest rank I could obtain without re-enlisting. They encouraged re-enlistment with a very large bonus of about $20,000—I respectfully declined. The additional education and my work performance resulted in increased proficient pay (non-taxed) and bonuses.

I used my military training to secure a position as a medical technician at the local civilian hospital in Elizabethtown, Kentucky. I worked nights, most weekends, and holidays. That type of work was a completely different world in the 1970’s. I was usually the only technician there. I took requests for tests, obtained the specimens needed, conducted the tests, reported out the results, and often completed the billing slip. Because of my knowledge in blood banking, especially in Rh incapability, I was consulted by treating physicians regarding those problems. My work also included performing EKGs, including emergencies in the ER and Delivery Rooms, as well as responding to codes (patients who had stopped breathing or their heart stopped). This position in the clinical laboratory gave me the incentive and opportunity to read most of “Todd-Sanford: Clinical Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods”.

There was still time, but not adequate, for socializing. Dianna and I played bridge with a group of friends from my unit, and went on picnics in the foot hills—should have made more time for this.

In my spare time, I took a few graduate courses in physiological psychology. The University of Kentucky offered extension courses on Post using some of the military staff as instructors. Our unit also had an experimental psychology group (that may be the subject of a separate story). Some of the officers from that group taught most of my courses. One of the instructors was a Captain Lloyd. It was his wife who had the appointment for induction to deliver their baby the morning my son was born.

There was one assignment I rejected, and about which I had not thought until relatively recently. During the hand-to-hand combat training section in Basic Training, I was recruited, interviewed, and offered a highly classified position. At the time, I was instructed that even the interview was classified, thus highly confidential. The position was described as one that reported directly to “Washington”. It involved long periods of time where my assignment would be so classified that I could not tell even family members, and that most of the work would be out of uniform. I respectfully rejected the offer, and did not think about it until years later when I saw the TV series “The Unit”. It was a series about a covert rapid response force that operated autonomously. I was not aware of any such unit in Army during the early 1970’s. I do not think the position offered was anything nearly as extreme as “Jason Bourne”, but it was enough of a black operation without details that it did not fit into my career path!

“What was your role in the military?” Over the approximately two and one half years I was stationed at Ft. Knox, we processed thousands of units of blood and blood products, trained hundreds of specialists in blood banking and immunohematology, and did some pretty good research.

What was one of the most difficult experiences during your time in the military, and how did you get through it

WARNING: THIS SECTION CONTAINS SOME GRAHIC DESCRIPTION OF THE CARNAGE OF WAR

“What was one of the most difficult experiences during your time in the military, and how did you get through it?” [WARNING: THIS SECTION CONTAINS GRAHIC DESCRIPTION OF THE CARNAGE OF WAR]

My difficult experiences with the military began before I entered active duty. A close high school and college friend dropped out of college, volunteered for Vietnam, and led a mortar team through some of the roughest battles in Vietnam the late 1960’s. On a routine patrol mission, one of his troops triggered a mine. He was brutally wounded losing the sight in one eye, severed ulnar nerve, hundreds of fragments of shrapnel in both legs. He developed hepatitis from contaminated blood (because there was not a reliable test to exclude hepatitis contaminate blood at that time). I visited him at Fitzsimmons Hospital in Denver several days after the injury. The orthopedic ward was packed like sardines in a can. There were beds or litters from wall to wall. To gain access to a bed, a series of beds had to be moved. The large sun decks were also filled with portable litters, all with amputees or major leg wounds. I cannot adequately describe how devastating this site of human carnage was. It was apparent that the staffing was inadequate. The suffering would last a lifetime.

A little biographical information is needed to more fully appreciate other difficult experiences directly attributed to the military. I was raised in a catholic family—my mother catholic and my father supportive and a later convert. My primary schooling was in a parochial school. My interests had always been in the biological sciences. With that background and that my personal philosophy included placing a very high value on life, not just human, I found terminating a life for any reason repulsive.

Initially, that was not the issue I had with Basic Training. Basic Training was directed to the lowest common denominator—the dullest tack in the box. I despised the draconian methods the drill instructors used, as well as the bias against anyone with an education. I learned very early on not to let them know I had a college degree. They designated those individuals for the worse assignments just to let them know everyone was equal in their eyes. I found it unacceptable.

On the first day of active training, we were introduced to a “small arms demonstration”. This included half a dozen M-16 rifles, a couple of M-60 machineguns, a couple of grenade launchers, a couple of handheld anti-tank rocket launchers, and a few claymore mines. That demonstration convinced me that anyone on the other side of that limited amount of firepower had to be crazy, crazy enough to try to kill me. I made up my mind then and there to limit the chances of putting myself in that position.

It was not until bayonet training that the true purpose of Basic Training really impacted me. The day when we affixed the bayonets and removed the scabbards, I got physically sick. For the first time, I realized that the true purpose of Basic Training was to learn to kill. As my bayonet’s edge glistened in the sun, I remembered how my butcher knife sliced through the hind quarter of beef to prepare a round steak, and realized that was what I was being asked to do to another human. That was a very graphic visualization I could not get out of my head. I also recalled all the traumatic injuries we were shown in the medic training. Traumatic amputations of limbs, sucking chest wounds, head wounds that maimed facial features, and eviscerating wounds to the gut. It took a while to accept that my training was necessary, vital if I was going to survive in a combat zone. Getting through that required several counseling sessions. My father even contacted the unit and I had meetings not only with the first sergeant and company commander, but also the colonel of the division. They convinced me to stay. Someone had to protect the Country. Even today, I still have that those images baked into my memory. Fortunately, I was never deployed to a combat zone, and never required to kill. Accepting that changed my perspective on life, and modified my behavior. It provided a much better understanding of the psychological trauma of those subjected to combat, and the difficulty many have readjusting to life after combat.

While I was at Ft. Knox, a very close friend, John North, Jr., was killed in a plane crash. Johnny was a pilot in the Air Force. He was extremely competent, and, in addition to flying a KC-135 tanker, he was an inspector for other tanker crews. He was on an inspection flight in Carswell Air Force Base, Fort Worth, Texas. His team was only inspecting the navigator and boom operator. After that inspection flight, according to Johnny’s father, that aircraft commander asked Johnny to stay aboard because he wanted to show this young pilot (Johnny) how to fly one of these tankers. During the landing, the aircraft commander brought the plane in on a “power off”, totally unauthorized for that plane. He blew them all away that day. Johnny had a four day old son. One more example of a tragic waste of life indirectly associated with “war”. You don’t get over this, just learn to live with it.

How did you feel when your military service ended? What did you do next?

When I left the army in 1973, it was with very mixed feelings. I had become very close to a number of the people with whom I had worked. It was a tremendous learning experience. I felt that the work we were doing would add substantially to the knowledge of medical care and treatment. But, I was anxious to get back to real life. I turned down a rather substantial signing bonus, $20,000 I believe, and a promotion. I didn’t hesitate to reject the offer. The other factor considered was that Vietnam was still very hot. It was highly probable that I would be deployed overseas, which may have included Vietnam.

When I realized when I was going to be discharged, I called the KU Medical School to inquire about application to that school. After learning I was in the military, they asked my age. When I told them, they said not to bother. I was too old to be accepted. It was disheartening. Several years later, age discrimination litigation eliminated this age bias and restriction on admission.

I then contacted Dr. Roger Fedde, under whom I had conducted some underground research that was of sufficient quality to be published in peer reviewed journals. He not only was amenable to taking me as a graduate student in the Department of Anatomy and Physiology in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Kansas State University, but arranged for me to be admitted without taking the graduate entry tests, and provided teaching/research assistantship. That reconnected a great friendship that lasts to this day.

What was one of the best parts about your time in the military?

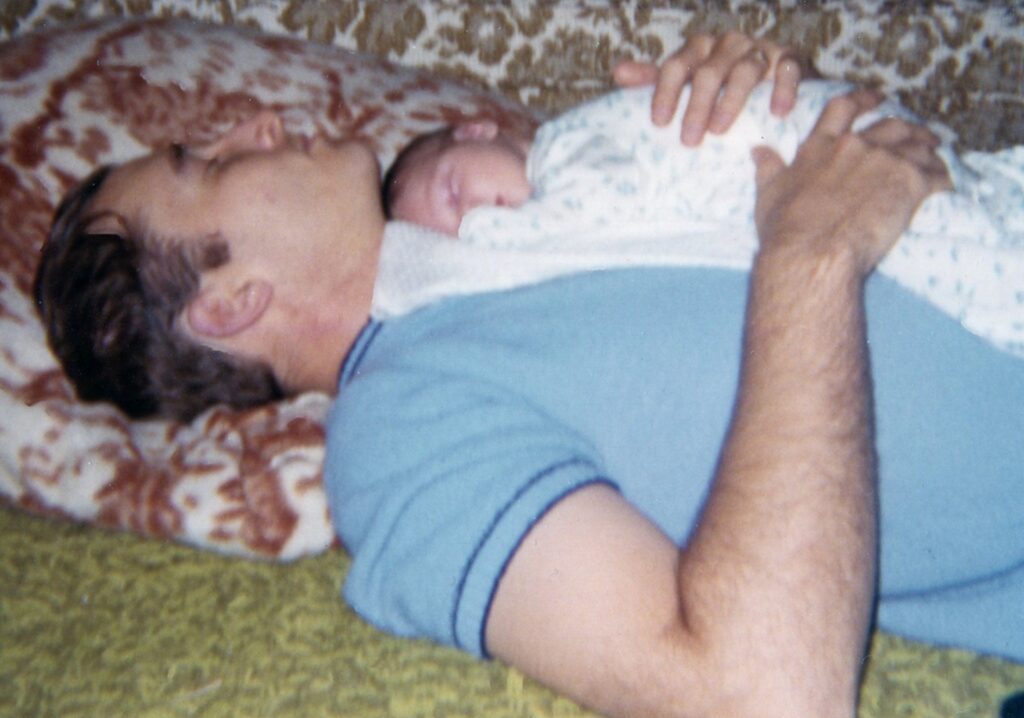

I covered most of this in the story on what I did in the military, at least from the military aspect. The formal and practical education and confidence I gained became extremely important in the rest of my life. But the truly best parts were more personal. My son was born in 1971 at Ireland Army Hospital. How could anything top that? The pregnancy and delivery were complicated. The pregnancy was an extra month—the doctors admitted to that only after delivery. The delivery was extremely complicated as described before. However, Jamie was a very strong baby and developed quickly.

Because he was a post-term baby, he had a head start when he entered this world. He was always alert, responded to people with a big smile, and developed the habit of greeting people with a raised hand with his index finger extended accompanied by a very big smile.

He started walking very early. At night, he would wait up for me to come home from my work at the Elizabethtown Hospital. When I entered the door, he would come running holding one finger in the air. We lived in a mobile home in Radcliff, Kentucky, between Ft. Knox and Elizabethtown during that time, and had very limited yard space. We did have access to public parks which we enjoyed. Dianna and I would take him to the parks where he loved to swing – it was never high enough, and spin on the merry-go-round. Those were the best parts of the military.

How do you feel your time in the military changed you as a person?

My time in the military caused me to become more focused, more dedicated to obtaining knowledge that would assist me in pursuing a career in biomedical research. I had become very knowledgeable in hematology, clinical laboratory techniques, and a developing field called immunology. I was committed, probably too committed, to consuming as much knowledge in graduate school as possible. I became very self-disciplined about my studies and work. I became totally engaged in my graduate work assuming (incorrectly) that others were onboard. I lost sight of some things that meant the most to me, without realizing it until it was too late.

Now, reflecting on that time, I think there was a hidden degree of guilt. Some of my best friends had either been killed or mutilated before they had a chance at life. I was well, healthy, and free to pursue my life. I think I felt an obligation to make the absolute most of my opportunities, opportunities they would never have.